Deciduous plants have evolved to be all about surviving the winter. We humans often describe ourselves as “hunkering down for the winter,” and perhaps we have learned this from plants that shed their leaves in the fall. But they don’t just dump their foliage willy-nilly. Before shedding those leaves, the plants reabsorbs nutrients like nitrogen and carbon from the leaves, storing them in their branches, trunks and roots to use for new growth in the spring.

Plants that are deciduous are able to shed foliage in the fall because they form a special layer of cells at the base of the leaf stem, called an abscission layer, which cuts off the leaf from the rest of the plant.

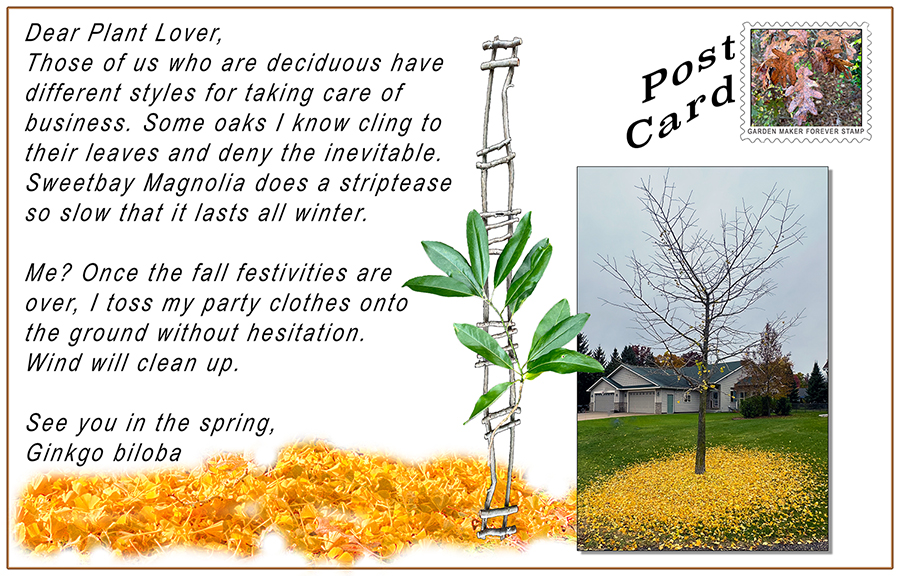

The timing and pattern of leaf drop in deciduous trees is fascinating – it reflects different survival strategies that have evolved over millions of years.

The basic trigger is similar across species: shorter days and cooler temperatures signal trees to form an abscission layer (a barrier of cells at the base of each leaf stem). This cuts off water and nutrients to the leaf, causing it to eventually fall. But the speed at which this happens varies dramatically.

Quick-droppers like ginkgos and many maples have evolved what’s essentially a synchronized shutdown. Once triggered, they complete the abscission process rapidly across all their leaves. This may be advantageous because:

- It minimizes the window when partially weakened leaves could be damaged by early winter storms

- The sudden carpet of leaves might help suppress competing plants near their roots

- It allows the tree to enter full dormancy quickly, protecting it from sudden temperature swings

Gradual-droppers like oaks take a more conservative approach. Many oak species (especially red oaks and some white oaks) retain dead brown leaves well into winter – a phenomenon called marcescence. Several theories explain this:

- The lingering leaves may deter browsing deer from eating tender buds

- Leaves falling gradually throughout winter slowly release nutrients back to the soil over time

- In younger trees especially, dead leaves may provide some insulation to branches

- It may simply be that oaks don’t “benefit enough” from quick dropping to have evolved faster abscission

There’s also significant genetic variation within species – you might notice one red maple drops its leaves a week before another nearby, even in identical conditions.

The strategy that works best depends on a tree’s native climate, typical weather patterns, and ecological niche. Neither approach is “better” – they’re just different solutions to the challenge of surviving winter.

0 Comments